Faculty and Administration Etiquette

Before we get to the main topic, I want to note that incoming students who are not in compliance with our immunization requirements received this message this afternoon.

I try to run this post each summer as we get closer to the start of the fall semester. Faculty etiquette is all about how your Deacs can put their best foot forward with faculty.

Tips for Students

A few years ago, a faculty friend of mine emailed me this article, U Can’t Talk to Ur Professor Like This. It is a great read, especially for incoming students, who are used to high school teacher etiquette and might not know how that differs in college. I have adapted some of the main ideas for the Wake setting:

ALWAYS call your faculty member Dr. [Last Name] or Professor [Last Name] – do not use Mr./Mrs./Ms. [Last Name] and never ever address a faculty member by their first name the first time you email/speak to them. Dr. or Professor are the proper forms of address. If your professor tells you it’s OK to call them by their first name, that is fine. But unless/until they do, they are Dr. to you, always and forever.

If emailing, you need to introduce yourself, use polite language, and close warmly. This means opening with a “Dear Dr. Jones,” and closing with a polite send off (“Thank you,” “Sincerely” etc.) and signing with your first and last name so your faculty member knows who you are (a faculty member could have five Scotts among all the classes she teaches, and the way our Wake email addresses are constructed does not always make it obvious what one’s last name is.)

Use a subject line so that your faculty member knows why you are contacting them.

Your grammar and punctuation need to be correct. You want to make a good first impression, so avoid typos. Also, avoid using shortcuts like UR for “your” etc.

Before you email a professor with a question, do your homework. The course syllabus is essentially the contract for the class – it tells students what the assignments are and when they are due, when tests/papers/quizzes are due, whether there is an attendance or class participation policy, what the grading system is, etc. When a student emails a professor to say “what happens if I miss class today?” and there is a clearly-stated attendance policy on the syllabus, that student is revealing that they have not done their homework in knowing their obligations for the class. That can form a bad first impression.

Be very careful of your tone. Email is a notoriously difficult medium to sense tone, and you want to make sure your message is not coming off as complaining, condescending, demanding. Write a draft, let it sit for a few hours, and then reread it to make sure your tone is professional and appropriate before sending.

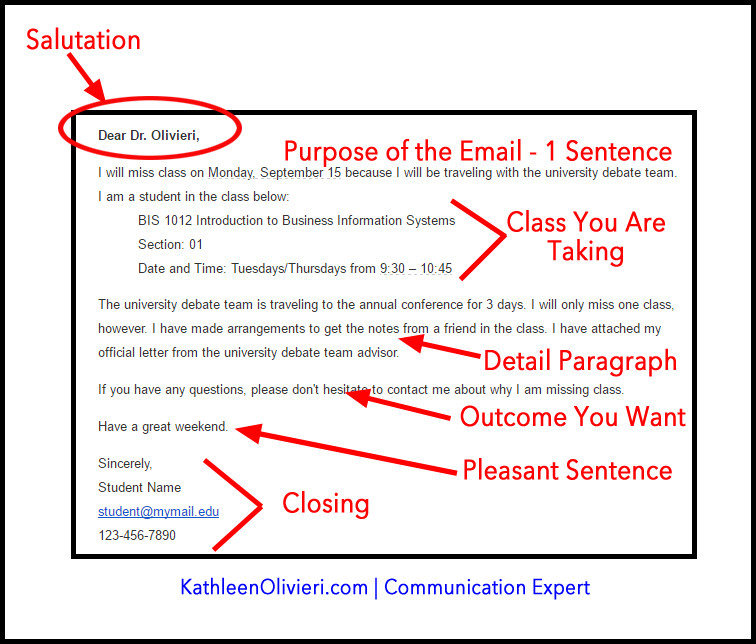

Here is one example of an email that follows these ideals (click to enlarge).

You may be wondering about why we are bringing up faculty etiquette: Why does all this stuff matter? or Why have nit-picky rules and formality? The article explains:

“Insisting on traditional etiquette is also simply good pedagogy. It’s a teacher’s job to correct sloppy prose, whether in an essay or an email. And I suspect that most of the time, students who call faculty members by their first names and send slangy messages are not seeking a more casual rapport. They just don’t know they should do otherwise – no one has bothered to explain it to them. Explaining the rules of professional interaction is not an act of condescension: it’s the first step in treating students like adults. [emphasis mine]“

There is a very comprehensive site from one faculty member from the University of Houston, who explains faculty etiquette guidelines for his students. It is a very worthwhile read, as it goes into many more details and situations your students might encounter.

Tips for Families

There is also some administration etiquette that families should be aware of. Sometimes, if a family is unhappy with X or Y, they want to reach out to the “person at the top” to give their feedback or ask for resolution of their issue.

In virtually every case, I would gently suggest that it would be better for your student to be the one to make that outreach, offer that feedback, etc. When students advocate for their own issues, they help build productive relationships with administrators; when families do it, it could send an [unintended] message that your student is not willing to engage in challenging conversations, or work on their own issues. That may have an unintended consequence of reflecting poorly on your student.

It’s also important to understand roles of major players on campus, because the “person at the top” is typically not engaged in granular detail on specific student situations. In very broad terms:

Presidents of colleges are typically responsible for the high-level vision and direction of their school, providing leadership for the institution.

Provosts are the chief academic officers, and typically work with the deans of individual schools on academic initiatives, research, ensuring effective teaching and technology, etc.

Deans of individual schools or programs typically work with the faculty of their school, the academic direction of their program, curriculum, etc.

There are other departments and staff who work with individual student (or family) issues, and those departments can be found on the Who to Contact for… page. Those offices are the place to start if your family has issues, because those are the people who can operationally work with your presenting issue, not our senior leaders.

And I advise families that you should never email your student’s faculty. I will have a more detailed explanation of this in a post next week, so stay tuned for more.

Knowing faculty and administration etiquette benefits both you and your student in navigating college life.

— by Betsy Chapman, Ph.D. (’92, MA ’94)

July 22, 2022