Etiquette

Today’s Daily Deac is about etiquette. There are all sorts of unwritten rules and social conventions in life, and some of these are widely-known, others you have to learn.

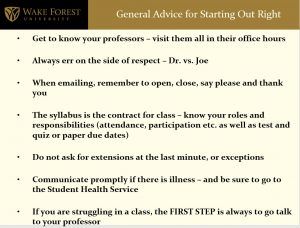

I’m a huge fan of not making people learn the hard way if you can instead be kind and tell things upfront that will help them. Every year when I meet with my new academic advisees at our first group advising meeting, I talk about some of the Dos and Don’ts of interacting with faculty – as seen in the slide at the right. Some of these suggestions might be common sense. But I want to talk about one particular piece today, and that is about how to interact with and address faculty, either verbally or via email.

common sense. But I want to talk about one particular piece today, and that is about how to interact with and address faculty, either verbally or via email.

A faculty friend of mine mentioned this article, U Can’t Talk to Ur Professor Like This, and it is worth a read – and a share with your students, particularly if you are a P’21 (or parent/family member of an incoming first-year student). Here are some of the key ideas from the article, reframed from my knowledge of Wake.

Students should always err on the side of respect when talking to their faculty. By this I mean, always refer to your faculty member as “Dr. Smith” or “Professor Smith” unless or until the faculty member says otherwise. One should not call a professor by his/her first name, or Mr./Mrs./Ms [Last Name]. Dr. or Professor are the proper titles. (Think of it like this – you would never call the CEO of your company – or your senator – or a judge – by his or her first name, you would use the title that office affords them).

Similarly, when emailing your faculty member (as with anyone else), remember that you are making an impression on that person, and you should be as professional and polite as possible. This means opening with a “Dear Dr. Smith,” and closing with some polite send off (“Thank you,” or “Sincerely” work well) and signing with your first and last name so your faculty member knows who you are (a faculty member could have five Andys among all the classes she teaches, and the way our Wake email addresses are constructed does not always make it obvious what one’s last name is.) It also matters that your grammar and punctuation are correct, that any questions you ask are clear and concise, and that you do not take an overly familiar, chummy, personal tone – keep that professional distance unless/until you have formed the kind of relationship where your faculty indicates more familiarity is allowed.

One perennial issue that my faculty friends at Wake and other schools tell me about is getting questions about things that are in their course syllabus. The course syllabus is essentially the contract for the class – it tells students what the assignments are and when they are due, when tests/papers/quizzes are due, whether there is an attendance or class participation policy, what the grading system is, etc. So if a student emails a professor to say “what happens if I miss class today?” and there is a clearly-stated attendance policy on the syllabus, that student is revealing that he/she has not done their homework in knowing their obligations for the class.

Why does all this stuff matter, and is this just a way for faculty to be nit-picky and overly formal? The article explains:

“Insisting on traditional etiquette is also simply good pedagogy. It’s a teacher’s job to correct sloppy prose, whether in an essay or an email. And I suspect that most of the time, students who call faculty members by their first names and send slangy messages are not seeking a more casual rapport. They just don’t know they should do otherwise – no one has bothered to explain it to them. Explaining the rules of professional interaction is not an act of condescension: it’s the first step in treating students like adults.”

All too soon, your students will be looking for jobs, or internships, or finding themselves in their first job. They will have to learn to navigate their work world – and the unwritten rules of that specific workplace – on their own. They will be better equipped for success then if they learn good habits now.

If your students want a deep dive into academic etiquette, the article references on faculty member from the University of Houston, who posts etiquette guidelines for his students.

PS – I am almost 47 years old and in graduate school. I am older than 90% of the faculty members whose classes I have taken. Still, I always, always call my professors “Dr. [Last Name].” You can’t unmake a bad first impression, so erring on the side of respect never hurts you, only helps.