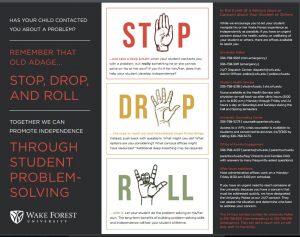

Stop, Drop, and Roll

One of the most difficult parts of having a student in college is when they have a problem and you aren’t there. When you live with your student at home and he/she has a problem, you at least get to see how he looks – you can gauge the degree of upset or stress using any of the million subtle markers you’ve come to recognize in your son or daughter.

At school, however, you get texts, or Instant Messages, or maybe a cell phone call. And those contacts can come at times when your student is upset about something – and it seems like it has taken on Epic Awful Disaster Horrendous proportions. All this makes parents and family members upset too – you’re now stressed because your student is stressed.

Or maybe the call is venting a frustration about having so many things to do (I have a chem test coming up, and I have a cold, but I also have to talk to some office on campus to figure out how to get X accomplished and I don’t have time to deal with all this!) and you think maybe you can help your student if you call the office in question yourself and take care of it.

In those times you are tempted to swing into action and jump in to help with your student’s issue, I’d encourage you to think before you act. Remember the old safety training – Stop, Drop, and Roll. What do I mean by this?

Stop – and take a deep breath when your student contacts you with a problem. Is it REALLY, something he or she cannot solve on his or her own? If you fix the problem for your student, has your student really learned anything or developed self-reliance and independence? Will your intended action help your student learn how to juggle multiple priorities and take care of things?

Drop – the urge to reach out and fix things yourself or provide detailed instructions on how your student should handle the situation. Instead, push back with questions: What do you think you might do? What are your options? What campus offices might have resources? What have you already tried? Who have you talked to about this already (your RA? adviser? etc.) Those kinds of questions can help prompt your Deac to figure out next steps (without you directing those next steps).

Roll – with it! This is easy to say, but hard to do. Let your student do the problem-solving on his or her own (even if the solution is different from how you might have handled it). Struggling with adversity builds resilience and helps your students learn that they are capable and resourceful.

We even have a handy graphic for this. Print it out and stick it on your fridge for those moments when you need it.

We even have a handy graphic for this. Print it out and stick it on your fridge for those moments when you need it.

I get a lot of phone calls from parents and family members who are worried about their son or daughter, and want some advice, but don’t want their students to know they are calling :) Normally what I advise is to sit back and wait 24-48 hours and not check in. In my experience, the vast majority of Frantic Phone Calls is the student venting his or her problems, and as soon as the venting is done, they feel better – and you are left holding the bag of worry.

For those parents and family members calling me to ask how to get X or Y done for their student, I also encourage them to let their student do all the legwork. Your student won’t learn how to navigate complex situations until he or she has to do it, which builds muscle memory and experience to draw upon for the next time. One day, instead of a chem test and a cold and a silly administrative task to complete, he or she might have a work deadline and a broken air conditioner and a sick child all at once. Having some experience in managing multiple things in college will equip your students to handle the adult challenges.

So if you call the Office of Family Engagement, and I encourage you to take a deep breath and Stop, Drop, and Roll, please know it is not that I am being uncaring. It’s that I believe your student has the wherewithal to fix the problem on his/her own, or needs to struggle through it and figure it out, which I promise will be much more beneficial in the long run than getting help from mom or dad or a family member.

Now OF COURSE if you believe there is a really dire problem that is of grave concern – imminent safety or wellbeing, etc. – you would want to consider taking a more active role.