Senior Oration: Conor Stark ’15 and MamaDear

The Daily Deac continues to showcase the finalists for Senior Orations. And with whispers of possible more snow to come this afternoon or tomorrow, we’re preposting Thursday’s Daily Deac just in case.

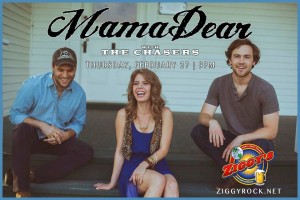

There is a basketball game scheduled for tonight (WFU vs UVA at 7 pm here at the Joel). A colleague in Athletics let us know that alumnus Parker Bradway (’11), a former Screamin’ Demon and member of Chi Rho, will be peforming the national anthem at the game Wednesday night with his band, MamaDear, as well as a halftime set. My colleague wrote: “MamaDear got its name from the last line of our alma mater, thanks to Parker! Having recently signed with entertainment-giant CAA, they were named the top up-and-coming band at the 2014 CMA Festival in Nashville. You can find information on them via Facebook and they have songs available on iTunes. Additionally, Parker and lead singer, Kelly, recently got married!” They are playing Ziggy’s here in town on Thursday, so your students who like country music can hear more.

There is a basketball game scheduled for tonight (WFU vs UVA at 7 pm here at the Joel). A colleague in Athletics let us know that alumnus Parker Bradway (’11), a former Screamin’ Demon and member of Chi Rho, will be peforming the national anthem at the game Wednesday night with his band, MamaDear, as well as a halftime set. My colleague wrote: “MamaDear got its name from the last line of our alma mater, thanks to Parker! Having recently signed with entertainment-giant CAA, they were named the top up-and-coming band at the 2014 CMA Festival in Nashville. You can find information on them via Facebook and they have songs available on iTunes. Additionally, Parker and lead singer, Kelly, recently got married!” They are playing Ziggy’s here in town on Thursday, so your students who like country music can hear more.

And without further ado…today’s Senior Oration is Losing Your Feet, by Conor Stark ’15.

— by Betsy Chapman

————-

I’ve always been struck by our desire to tell stories. It truly is one of the most peculiar facts about human beings, namely that—for some reason—we feel compelled to understand and be understood by one another. In our best stories, it seems to me that we keep returning to three questions in particular, questions which confront any reflective human beings: namely (1) who am I, (2) why am I here, and (3) how, then, should I live? And so we look stories to provide the context in which these questions can be asked and answered effectively. They tell us how we can understand the world around us and how we might relate to it in a meaningful way, in a way that might make our lives happy and whole. Who better, then, to hear such stories than college seniors, those of us who are about to wrestle with uncertainty, whose business it is to contend with the future? Indeed, we must not deceive ourselves here, we must admit that, although we may be anxious, uncertain perhaps, we, as befits our age, are also full of hope, which may lack a name as of now, but which bears all the marks of passion and resolve. (Pause) While only a foolish person approaches his life without anxiety, only an ornery one does so without hope, without that uniquely human hope that at the end of every story, lies a conclusion and a meaning. But perhaps it would be better to show such stories, as opposed to telling you about them.

One night, a man was seen walking outside of a town near Athens. In the sixth century, the night brought its necessity with it. It was time when meaningful labor ceased, when tired hands put down the plough and reached out for home. But this man’s day was just starting. It was as if the night’s warning was lost on him, as if he saw freedom where others had seen only compulsion. To many, it seemed that man was in the habit of talking to himself. But how differently he understood himself. As a child might wait under his covers, eager for his parents to come and finish yesterday’s story, so too this man waited upon the stars. If they had descended, he would try to speak with them for a while. But no secrets would be shared that night, for in his passion to shine a light onto heaven, the man tripped over his feet into the dark and fell head first into a hole in the ground. Justice had been served—and the night had claimed its due. Thankfully, a young girl came to his aid, and, after lifting him up, scolded him for his folly. The man’s name was Thales, and he was, by most accounts, the first philosopher. As of that moment, he succeeded in establishing what would be a long and glorious tradition of Western philosophy, of posing odd questions to yourself and seeming odd to just about everyone else. Being a philosophy major myself, I must acknowledge the truth in this story: one day, for example, I got so caught up trying to figure out how minds were related to bodies, I neglected the fact that my body was at once, hungry, tired, and several hours late to dinner.

Of course, these stories are comical. The person who forgets that he is on earth, although trying to storm heaven on top of syllogisms, is no doubt ridiculous. However, I’ve come across another story lately, one that is perhaps more tragic than the other comical, a story which has unfortunately become more commonplace and acceptable to us. A certain man was born, raised, and married in the company of good people. As he made his way through life, he made a reasonable amount of money, kept a reasonable number of friends and acquaintances at hand, and maintained a reasonable home life with his family. The man’s life passed quietly in this fashion, and, after he had died, everyone decided, as if by committee, that the man had lived a long and happy life, that others could only be so fortunate to have half of what this man achieved for himself. He was, in the end, a good person, who minded his own business and left his eyes on the ground, on life’s problems and demands. And yet, something happened to the man during his life that was most unfortunate. The man had forgotten or had allowed himself to forget that he had never known himself, had never known whether he was a good or bad person, or had lived the right kind of life. While Thales had neglected the ground beneath his feet, our honorable man had lived his entire life unknown to himself, neglecting a need he had always felt, which had always made him a bit uneasy.

In the Symposium, Plato has someone say that, underneath every passion and every love, lies a desire for happiness and for good things. In his words, “love always wants to possess the good forever, [since] that’s what makes happy people happy.” Indeed at the end of our striving, whether for money, grades, security, friends or family, lies a desire to be happy. And there we can go no further, since if someone were to ask you why you wanted to be happy, you would rightly respond, ‘What do you mean, why do I want to be happy—I just do’. But it seems we’ve omitted a few things. For don’t we say that courage makes someone happy? What about justice, moderation, or wisdom? Surely we don’t call the person happy, who in cowardice shirks his duty, who, through intemperance, cannot control his actions, who, because of ignorance, stumbles recklessly through life? It seems, on the contrary, that, if we want to be happy, we need virtue. That’s a good thing, too, since, although other people may rob us of our wealth or tarnish our character, the virtues are lost only through negligence. It’s curious, then, that, while the virtues are so essential to our lives and to our happiness, they have been so unceremoniously abandoned.

Recently, we have talked about the differences between races, genders, and classes, and have asked ourselves many questions in favor of those suffering injustice. How can equality be won for this group? How can we give freedom to crowds of disenfranchised people? Valid and difficult questions no doubt, but are there not also questions with a different sort of character? Questions that, as it were, take it upon themselves to search through the crowd, saying nothing to the group, but saying everything to individual, overlooking entirely the issues of gender, class, or race? Indeed, these questions find every man in the protest, every member of the cause, and whisper to him “are you the person you should be, are you living the right kind of life?” In short, they take us aside one by one, in order to examine each of us about virtue and what it means to live a good human life.

Pascal said that mankind’s problems, for the most part, would be solved, if we could all just learn to sit quietly with ourselves, alone in our rooms. While not that drastic, I’ve often wondered what kinds of misunderstandings and injustices we might avoid if, instead, we focused on being understanding and just people, in whom we might see the virtues of wisdom and justice at work. While it is not wise to lose one’s feet or forget the world’s problems, it’s certainly far more foolish to wander through life without stopping to look at oneself properly—to examine whether one’s life is good and happy. For it is this reflection, this refusal to be deceived by oneself, and this love of excellence, which makes, and has always made, a human being a human being.